Cycling SumatraThe first thing you notice about the Sumatran countryside is the lushness—every shade of green imaginable—lime-green ferns, pastel fan-palms, deep-green mango trees, luminous-green rice paddies. For a cyclist, this is the green light—a tropical wonderland to be savored at a slow pace. Unfortunately (from the cyclist's point of view), Sumatra is rich in oil and natural gas—and rubber. Gasoline is dirt-cheap and so is public transportation: Japanese and Korean trucks, vans and buses hurtle along at reckless speeds. Our tour leader, Patrick Morris of VeloAsia, is nervous: he doesn't want any cyclists sideswiped, or worse. Seven North Americans, including myself, are guinea pigs in a two-week exploratory tour of Sumatra, the largest island in the Indonesian archipelago.

The apprehensions prove unfounded: with some judicious shuttling of bikes and cyclists by tour-van, we skip the heavily trafficked sections near major cities and stick to lesser-used routes. When cycling, we quickly adapt to the bizarre antics of Sumatran drivers (sudden stops by passenger vans, daredevil overtaking at blind corners). It's a matter of predicting the drivers' maneuvers, riding to a different rhythm, getting used to new "rules." You can even get used to the heat, too—riding on through the Sumatran mid-afternoon "sauna". And there's plenty of lake-water and refrigeration along the way to help chill out. In other aspects, Sumatra is ideal for cycling—the Dutch engineered a road system to exploit Sumatra's plantation wealth (rubber, tobacco, spices), and the present roads, though narrow, are in excellent shape. The most important factor of all? The people of Sumatra. They're super-friendly—warm, honest, curious. Sumatra is a melange of tribal groups—Karo, Batak, Minangkabau. The people make the trip very special.  A van shuttle from motor-mad Medan to laid-back Berastagi puts us on square one for cycling. At over 4,000 feet in elevation, Berastagi is a region of crisp mountain air—in the 1920s it blossomed as a hill resort under the Dutch. Dutch cottages are dotted around; to the north of town is the former country club, complete with 9-hole golf course and cracked tennis courts—all now incorporated into Bukit Kubu Hotel. A curious legacy from the Dutch: Western vegetables such as carrots, which grow well in the rich volcanic soil. After a day trip to the still-smoking volcanic caldera near the summit of Mt. Sibayak, we are ready to ride. And ride and ride. Patrick has miscalculated the mileage to Lake Toba (or rather, relied on faulty map data) so the first day is a blistering 80 miles of rolling hills instead of the predicted 60 miles. Where the jungle parts, there are magnificent panoramas of Lake Toba—and these vistas draw us on. Lake Toba is Asia's largest lake—some 60 miles long and 18 miles wide. In the middle sits Samosir Island, which is roughly the size of Singapore, to give an idea of scale. In the early 19th century, Lake Toba had a near-mystical aura—it was sacred to the Batak people, so the approaches to it were jealously guarded. The first Europeans to lay eyes on the lake were two British missionaries, in 1824. Exploration of the area was hampered by the Bataks: several Western missionaries who found a way in accidently shot a Batak woman—and were eaten on the spot in reprisal. The Bataks dealt with lawbreakers and enemies in this fashion, sometimes with public cannibalism. What astounded Europeans was the fact that these cannibals could write: the Bataks developed a script for recording medical cures and other important data—stored in concertina bark books. Ultimately, Dutch and German missionaries prevailed—Batak country is mostly Protestant (although with a strong undercurrent of animism).

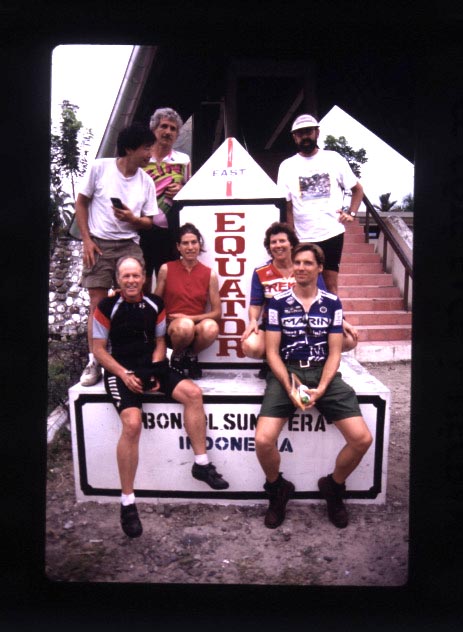

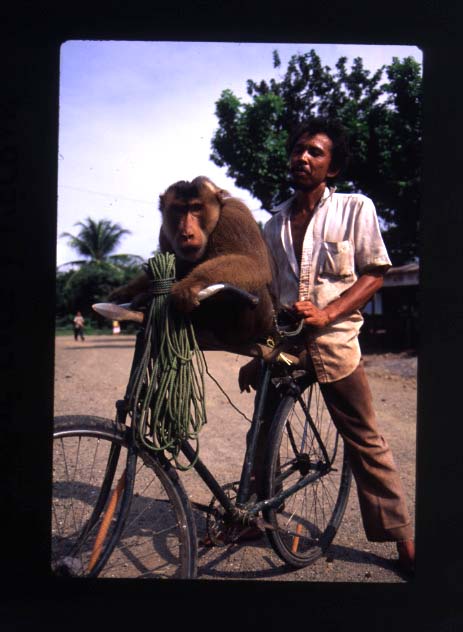

On Monday morning we board a small ferry to cross Lake Toba to the village of Haranggaol. There are hardly any tourists, but certainly tons of onions. Buyers in Medan arrive in Haranggaol twice a week to buy produce that arrives by boat from all over Lake Toba. Muscular porters scurry around with sacks of onions, and women in bright headdresses haggle over prices. The air is redolent of onions, and the fragrant smell of mangoes and passionfruit—and the sharper aromas of garlic, cloves and kaffir limes. At Haranggaol you can also find the culinary specialty of the region—goldfish. Well, actually, it's a large gold-scaled fish which is fattened up in holding-pens at the lake-edge—and very tasty, too. The women vendors at Haranggaol have positively vampirish smiles—they constantly chew wads of tobacco, and a betel-nut mixture that stains the mouth a bright red. Chewing betel nut is supposed to make the teeth strong, but the gap-toothed grins of older women tell a quite different story. South of Lake Toba, we join the Trans-Sumatra Highway—the road that runs the length of the island, covering some 1,500 miles. We have been avoiding this route for traffic reasons, but traffic turns out to be lighter than expected, and we have adapted to the tactics of Sumatran drivers (except for the odd airhorn in the ear as a way of greeting!). We pass through small towns with double-storied wooden buildings lining the main drag, like movie sets for the old Wild West frontier. And to reinforce the image: the odd horsedrawn cart with wooden wagon wheels, and cigaret billboards that seem entirely inspired by the American mid-west lifestyle. The countryside oscillates from dense jungle terrain to cultivated land. Along the roadsides near plantation belts are drying crops—rice kernels, coffee beans, and the bark of the cinnamon tree. Splotches of color in the greenery: red of hibiscus, white of frangipani, purple of bougainvillea, and the most striking of all—a variety of palm with bright orange stems. Another day of riding southward puts us right on the equator, where we're beseiged by "I-crossed-the-equator" T-shirt vendors, outside of Bonjol. A pause here while we ponder whether beer swirls down the gullet clockwise or counter-clockwise, and what effect this has on the digestion. For this experiment to work properly, you need to drain a large volume of liquid—and today is certainly hot enough to try! Which brings me to food. After a hard day of sweaty cycling you're ready for a hot meal, right? When they say HOT here, they mean it. The specialty of West Sumatra—Padang food—ranks among Asia's hottest. You sweat again, but it sure clears up your sinuses in a hurry. Ordering is easy—give the waiter the word and he comes back juggling a dozen plates of meat and vegetables, all laced with chili pepper. When you're through, the waiter examines the left-overs to figure out the bill—you only pay for what you've actually eaten.  Sweat glands get a good workout on this trip—one minute you're in the "Sumatran sauna", hot and sweaty and dusty—and the next, you're sitting in an air-conditioned support van, gulping iced water. But while the bus is comfortable, it is also sealed and insular: the bicycle brings you in close to the smells, the sounds, the heat, the people—the real experience. At dinner time, the peppery Padang food reactivates the sweat glands and sends you off in search of a cold beer or an ice-cream. Thus ends another day crammed with new experiences. And so to bed. Where a Dutch wife sometimes awaits. Yes, that's an extra "body pillow"—a long tubular bolster (originally from Java) that the Dutch claimed absorbed the sweat from the back of the legs. No-one believed this: the pillow became known as a Dutch wife—a knee support, and the butt of ribald jokes. If you're smart, you go to bed early in Bukittinggi—we're now in Minangkabau country. The Minangkabau are mostly Muslim ("flexible Muslims" according to a local guide) and the pre-dawn call to prayers is broadcast loud and clear through minaret loudspeakers of the many mosques. Riding is better in the cooler dawn hours anyway: we get off to an early start for Lake Maninjau. This is a spectacular day of riding through the Minang Highlands—I have the eerie feeling of being incorporated into a classic still-life painting. Rustic communities toil in quiet harmony with their surroundings; the landscape is Asian—coconut, jackfruit, clove and cinnamon trees—but the housing is vintage Dutch. There are white wooden cottages with brown shutters—the original tile roofs long replaced by corrugated tin. And here and there, small mosques with domed silver or green roofing. An exhilarating descent, gliding down a set of 44 bends engineered by the Dutch—to reach the shores of Lake Maninjau.  At this lake, Dutch colonial architecture is everywhere—probably for the very good reason that the lake has an entrancing setting, backed by jungle-covered mountains. At lunch we meet an elderly Swiss couple who used to holiday in this area. They recount the demise of the Dutch plantation owners in Sumatra with the coming of the Japanese in World War II. The Swiss woman describes a sight that stays firmly in her mind: the first Japanese soldier arriving by bicycle, then another, then two more, then ten more—and soon hundreds more. As Swiss nationals, the couple were not imprisoned by the Japanese, but were placed under virtual house arrest—not allowed to leave Sumatra, either. There's much to explore around Lake Maninjau—trails to hillside villages are rideable on a mountain bike. You can even ride the edges of rice paddies, taking in snippets of village life—water buffaloes lolling in the mud, farmers threshing rice or plucking red chili peppers from bushes. Or you might come across some monkey business. A man trundles down the road with a barrel of coconuts and his faithful assistant, a monkey. The monkey shimmies up a coconut tree with a long rope attached (to ensure no escape)—the man barks a command and the monkey twists off ripe coconuts and sends them to earth. More monkey business on the final ride toward Padang—some monkeys are kept on porches as pets; some swing overhead in the forest canopy, wild and free. Riding down the road, we pass a man riding a bicycle—and do a double-take. His passenger, sitting on the back rack, is a large rhesus monkey. It's another coconut work-crew in transit.  And finally, our cycling trip almost over, we head for the city of Padang, a port under the Dutch in the days when Sumatra was the world's leading pepper producer. At the end of the trip, a celebratory dinner—and time to take stock. The road has offered much that intrigues. We've covered some 500 miles—half by bicycle, the rest by van—but what we have seen is really only a "slice" of Sumatra. The trip has whetted the appetite, leaving us hungry for more—and leaving us with the distinct impression that there's much more out there to explore. Michael Buckley is author of Vietnam, Cambodia & Laos Handbook (Moon Publications, 1996). Whenever he gets the chance—as in Sumatra—he likes to cycle through Asia, as it brings local life into sharp focus. TRIP HIGHLIGHTS

Casualties: Larry and Patrick arrive slightly bruised after a forced feet-up crossing of rapid Bohorok River. Richard gets scratched up after an acrobatic backflip off a ravine to catch a butterfly. Larry plants himself in the mud of a rice paddy. Layne inadvertently explores a swamp by bike. All injuries non-bike, except for Larry's mud-plant and Layne's swamp dive. Up Front Award: to Bill, who went so fast he lost his cyclometer. What drove him on? Was it the powerbars? Was it the gado-gado? Or was it the carbon-fiber Canondale with the dual suspension? Culinary Highlights:

Ready to join a bicycle tour of Sumatra? Contact VeloAsia. Michael Buckley is author of the newly-published Heartlands. He has also written the Tibet Travel Adventure Guide, Moon's Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos Travel Handbook, Cycling to Xian , Tibet, and has guided VeloAsia tours in Sumatra and Vietnam. |